Across the country, one in four cities reported being attacked by cybercriminals every hour. That’s according to a 2016 survey, but attacks against cities have since risen.

Cities in Texas are often targets of cyberattacks, especially small cities, which often lack personnel and funds.

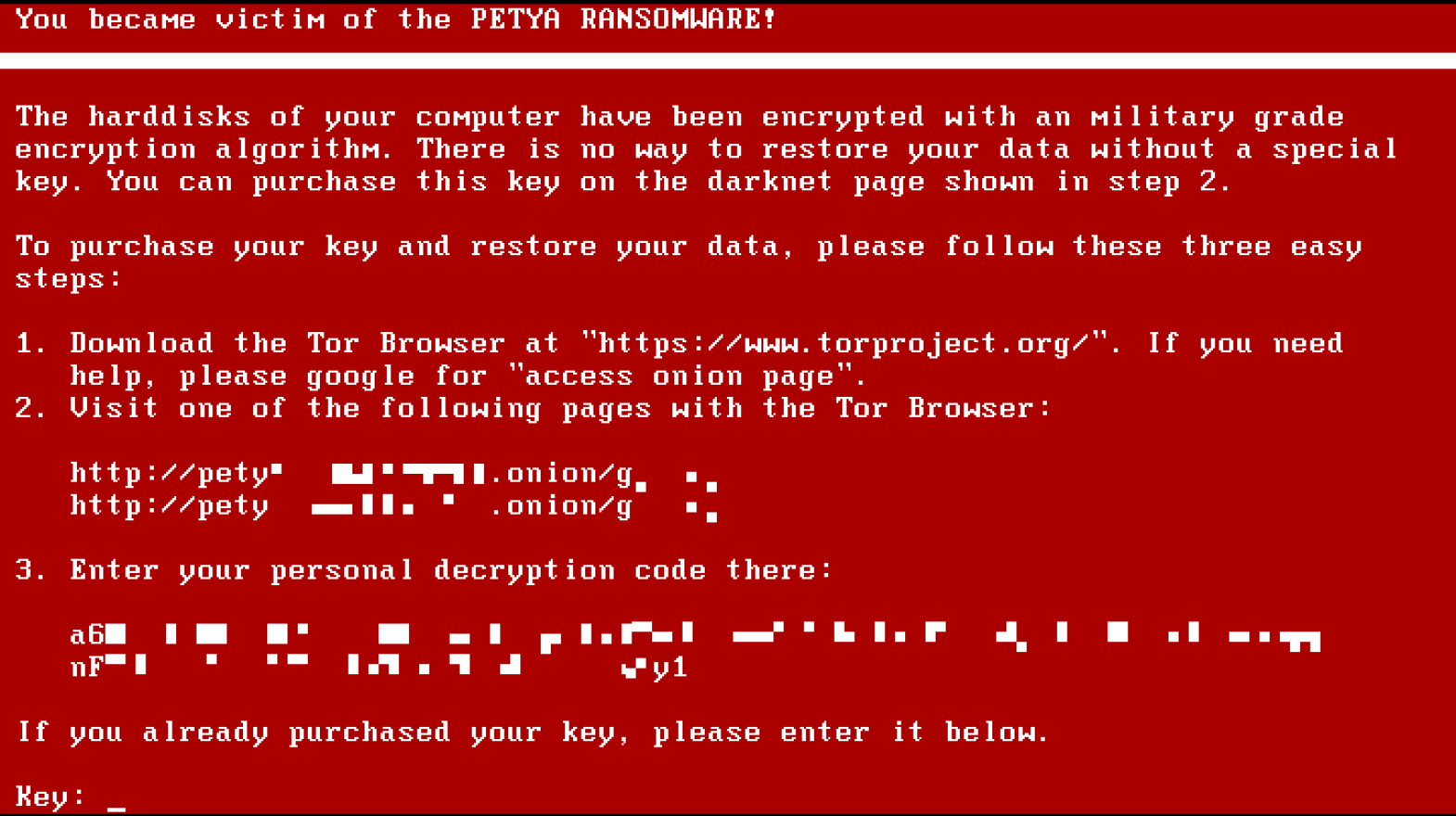

For example, last May, cybercriminals broke into the computer network serving the city of Shavano Park. Criminals took 2.1 terabytes hostage in a ransomware attack — including 58,000 financial and accounting files. It knocked a police server offline, which impacted basic reporting.“Typically when a cyberattack happens, no one dies. Nothing blows up. Nothing is lost, but it impacts the operations of all city departments,” said Curtis Leeth, assistant to the city manager.

At the time Leeth was the only cybersecurity or IT person on staff, and those duties made up only a third of his job.

“There remains a persisting capability gap in our ability to confront the clear and present danger of cyberterrorists and cybercriminals,” said the city in a January application for cybersecurity grant funds.

Shavano Park is around 3,000 people and encircled by San Antonio’s northwest side. Even though the city is small, they have information like employee health data and social security numbers that bad guys want or can ransom.

“All we are on the internet is an IP address or a domain…” he said. “They’re just looking for open ports, unsecure networks.”

Many cities like Shavano Park lack the resources to combat the cybercrime problem. A 2017 report to the Texas legislature said only 200 of the 1,100 cities in Texas had a full-time cybersecurity employee. Some turning to volunteers to do the work.

Ultimately, Shavano Park recovered the data unaltered, but Leeth said they wouldn’t have been able to do it without outside help.“And at that point— at least for a small city like me— that’s beyond my capabilities.”

Shavano Park turned to the the Texas Municipal League, an advocacy and resource organization for Texas cities. The city had cyber extortion insurance through the league, and it also provided legal advice and referrals for federal and state resources.

Shavano Park was assisted in turn by the as well as US Homeland Security’s Program.

San Marcos, Sugar Land, Tyler, Cockrell Hill, Houston, Del Rio are just a few of the cities breached in recent years.

TML’s cyber extortion liability insurance received seven claims in the first quarter of this year, on pace to double last year’s 13 claims.

But TML doesn’t insure everyone. Cities like Dallas and Houston have from elsewhere.

So getting a complete picture of breaches in Texas is difficult. The state and the public learned about the city hacks largely because the press reported the incident.

While the number of hacks and attacks are going up, don’t expect cities to talk about it said Sid Hudson, chief information officer for McKinney, Texas.

“Some of these cities that do experience an attack. They will go underground, and they won’t even communicate with their closest peers for fear of something leaking out and being attacked further,” Hudson said.

Hudson is also president of the Texas Association of Governmental IT Managers, an organization that encourages pooling knowledge. He said many do, hoping to share best practices and alert one another of possible schemes.

But some don’t, and even Hudson is wary of talking publicly about how Texas cities are faring.

“I’m sorry, I’m not comfortable with talking about that,” he said when asked about how cities are attacked.

Hudson said he doesn’t want to make it worse, and he said stories like this one may advertise vulnerabilities.

Cities notify people when their data gets stolen but aren’t required to report to the state.

“We don’t know what we don’t know, and I don’t think we know a lot,” said Giovanni Capriglione, a Texas House member from north Texas.Capriglione authored a bill that passed out of the House May 1 that addresses the issue in part. Among other things, mandates cities report breaches to the state, requires cities join regional cybersecurity information sharing organizations and creates state matching funds for local governments.

Capriglione helped pass legislation dealing with hardening the cyber infrastructure of state agencies last year.

“Local cities, municipalities and counties are probably our most at-risk entities,” he said.

He chaired the now-defunct select committee on cybersecurity. In that role he heard about cities who didn’t know they were breached six months after an attack, and about cities that hadn’t removed former employee logins in twenty years.

“I was just overwhelmed by the number of cities who said, ‘Hey listen, I just need someone to talk to. Someone I can have help,’” he said.

A 2016 survey from the international City/County Management Association or ICMA showed the biggest barrier to cities beefing up their cybersecurity was funding.

“It’s a budgeting dilemma that every local government has,” said Cory Fleming, a senior technical specialist for ICMA. “What do we spend money on this year? Do we spend it on roads or do we spend it on children’s programming parks and rec?

The lack of personnel means cities may take less precautions. That’s what makes them targets, she said.

“Sometimes we get caught up in thinking that we have to have the greatest technology, and it’s really the human factor and making sure that we have our people trained,” said Fleming.

Making small steps like finding free or state-sponsored training and getting liability insurance makes a difference.

For Texas to make progress, many are arguing cities first have to talk about it.

Paul Flahive can be reached via email at Paul@tpr.org or on Twitter .

Copyright 2020 Texas Public Radio. To see more, visit . 9(MDAxODQzOTgwMDEyMTcyNjI4MTAxYWQyMw004))