Warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual assault.

Sexual assault is a crime that can happen to anyone, but women are twice as likely to be victimized in Texas. , UT Austin’s Institute on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault found 1 in 5 men will experience some form of sexual violence in their lifetime. But for women, it's 2 in 5.

That’s nearly 6 million women living in Texas today.

Yet when it comes to reporting this crime to police, only around 9% come forward.

SUBSCRIBE | Find The Provability Gap on , or

Over the past few months, I interviewed and five other victims who reported their assaults to Austin police. (The average number of adult sexual assaults reported to APD is roughly 500 annually, according to numbers provided by the department.)

Even though each of the crimes was different, the women had similar criticisms for how their cases were handled.

None of the victims, save Garrett, felt police believed them. Pull up any news report about sexual assault and you’ll likely see this same concern echoed by victims across the country. While of reported sexual assault allegations are false, victims still feel too many law enforcement officials are defaulting to disbelief. And the worry is not only in their heads. Historically, not believing women has been baked into the law itself.

Even the most well-meaning detectives can believe a victim is lying if they’re not trained to spot signs of trauma.

“Most people think that if you experience a rape, or an attack of some kind, that people are going to run away or they’re going to fight back, but that’s traditionally not true,” said Kristen Lenau, co-founder of the Survivors Justice Project.

For more than a decade, Lenau has been working with people who have been affected by violence and trauma. She says victims tend to experience rape as a life-threatening incident, which means they will have some sort of survival response. This includes flight, fight or freezing.

“People will do what they need to do to survive,” Lenau said. For women, in most cases “that means a sense of tonic immobility, or a freeze response."

Even if a victim doesn’t freeze, law enforcement can still misconstrue other aspects of an encounter if they’re not .

Take the case of Emily Borchardt. In 2018, she was strangled, abducted and sexually assaulted by three men over 12 hours. According to the police report, her detective, Dennis Goddard, failed to get a copy of the surveillance video from the motel where she was taken and did not collect any evidence from the room where she was raped.

Police were able to identify the men. But according to police reports, Goddard said he thought parts of the attack sounded consensual. Even though hospital reports show she had bruising all over her body, Goddard said, because she complied with some of her attackers’ demands, police couldn’t make a case. (KUT reached out to APD for comment, but a spokesman said the department could not comment because of the pending lawsuit.)

Her case was declined prosecution.

“Everything she did to minimize the harm done to her was kind of held against her,” Sarah Borchardt, Emily’s mother, said. “If she had had more physical injury they probably would have been more willing to go forward with it.”

But Borchardt’s actions were in line with how many victims respond when undergoing a trauma of this magnitude. Lenau said when someone fears for her life, she will do whatever she thinks will keep her from further harm.

“Whether that’s giving someone your wallet if you’re being held up [or] whatever it is,” Lenau said, “if we feel overwhelmed and threatened beyond our capacity, we will go along with things to protect ourselves."

Trauma can also affect a victim’s memory. Garrett said she can’t remember large chunks of time from the night she was attacked, and it’s only slowly starting to come back to her. Lenau said this is common with most victims’ recollections of an attack.

“They come out like fireworks,” she said, usually when some event, person, word or scent triggers a bit of recollection. But some victims may not recall anything for years.

“Law enforcement are typically and traditionally trained to interrogate suspects,” Lenau said. “There is not a lot of built-in training into this culture – and into this profession – around interviewing victims."

The (SARRT) conducted a 2018 study to better understand the community response to sexual assault. It interviewed 75 people, including sexual assault victims, law enforcement officers, advocates and attorneys. A large majority of participants expressed a need for trauma-informed training among patrol officers, detectives and prosecutors.

The Office on Violence Against Women at the Department of Justice defines trauma-informed care as identifying and limiting potential triggers to reduce retraumatization. In other words, it’s a form of sensitivity training.

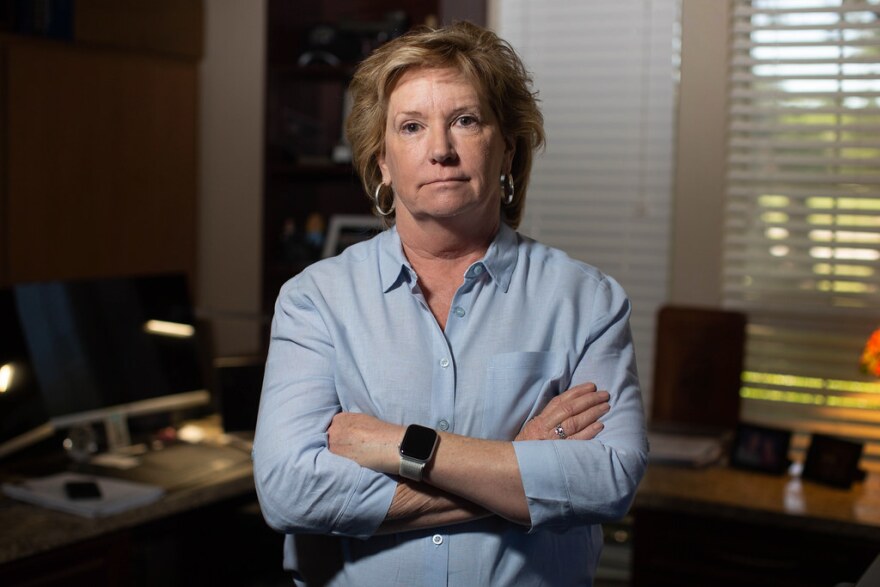

“If you don’t understand how deeply personal the crime of rape is, then you don’t need to be doing this work,” said Elizabeth Donegan, a 26-year veteran of the Austin Police Department and former head of the APD Sex Crimes Unit.

After retiring from APD, Donegan became known as one of the country’s leading experts in how law enforcement responds to sexual assault. She’s also been critical of the Austin Police Department’s handling of these crimes. Last year, she was interviewed for in which she accused APD of pressuring her to exceptionally clear cases she says should have been suspended or left open.

Donegan said after she refused, she was eventually removed from the unit. Her claims were later confirmed by a state audit that found APD . Donegan is now running for Travis County sheriff.

“We have to retrain ourselves in law enforcement to understand that the victims’ behavior is going to be completely different than our expectations, because of trauma,” Donegan said. “Trauma plays an important and critical piece in these investigations, and you have to be trained to understand how trauma presents itself.”

APD said it does send new recruits to a conference that provides trauma training. But most experts would agree one training in the first six months after an officer is hired is likely not enough.

Another criticism victims shared was that they rarely, if ever, received updates from their detectives about the status of their cases. Donegan said this is because the Austin Police Department is facing a problem seen across the country: the sex crimes unit is woefully understaffed.

Right now, APD has 17 detectives in the unit, but four are assigned to cold cases, including those attached to more than 4,000 backlogged rape kits that were finally . That leaves only 13 detectives to work on incoming cases.

According to Austin police, there's an average of 760 child and adult sexaul assault cases reported each year. That's more than 60 cases a year for each detective –and that's not including investigations carried over from prior years.

To put that in perspective, Austin’s homicide unit has 12 detectives and works an average of 30 murders a year.That means about two to three new cases per year for each officer.

“I believe all of those investigators and the supervisors want to do the right thing and will do the right thing ,”&�Բ�����;Donegan said. “But when you’re overwhelmed, you’re understaffed … you’re just triaging.”

Throughout the two years her case was pending, Garrett said, the only time she got updates from her detective was when she called herself.

“I called my detective all the time. All the time,” she said. “I cannot stress that enough.”

Sexual assault survivor Hanna Senko echoed these complaints. She said her case was “a typical date rape scenario” in which a man spiked her drink and she woke up the next morning with no memory of the evening. Senko said she immediately reported the attack to police, but the entire experience left her jaded.

“It’s largely a wait-and-hear-back game,” she said. “I had to place many phone calls trying to get information, over several months, and so it was a pretty disappointing process.”

Donegan says this lack of communication is a problem and can lead victims to drop out.

“But as an investigator, if you have 15 cases that you’re working that month, you’re just doing what you can to keep your head above water,” she said.

Austin Police Chief Brian Manley said he is aware staffing is a problem and expects the city’s review of sexual assaults will come to the same conclusion.

Donegan says all the training and resources in the world won’t help lead to more prosecutions, however, unless police departments start prioritizing the more difficult, and more common, types of sexual assault cases: those in which a victim knows her attacker.

Sarah Jones is one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit against the City of Austin and Travis County. (She chose to use a pseudonym to protect her identity.) One night in 2017, she says, her ex-boyfriend drunkenly came to her house, yelling outside her door. He refused to leave. Her son was sleeping, and after a while, Jones let him inside. She said she'd call him a cab.

They began to have consensual sex, but it turned violent. He strangled her and raped her anally.

“He hit me so hard across my face that not only did I have bruises across my neck from the strangulation but I had a handprint across the side of my face,” Jones said. “I thought my eardrum had burst. It was excruciating.”

When it was over, she said, she ran to the room where her son was sleeping and locked the door until her ex left. The next morning, Jones called APD and got a rape kit. Even though her attacker was arrested within a month, Assistant District Attorney Beverly Matthews decided not to move forward with the sexual assault charge. Authorities did move forward with the strangulation charge, but that was ultimately dismissed.

KUT reached out to the Travis County DA’s office for comment but was told employees could not respond because of the pending litigation.

Jones said she remembers her prosecutor telling her she was not a credible victim because of a past arrest in which she hit an ex-boyfriend who made fun of her son’s speech impediment. She received three years’ probation.

“They took my case for one punch – that didn’t even cause any injury – so seriously,” Jones said. “Because of that, I was [not a credible] victim.”

Even though Jones is the only plaintiff in the class-action lawsuit who knew her attacker, cases like hers are more typical.

UT Austin’s Institute on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault found that 70% of sexual assaults in Texas are committed by someone known or related to the victim. (In Austin, that number is around 90%.) But researchers at say most people, including some detectives and prosecutors, still believe are committed by strangers.

“They think sexual assault is the bad guy jumping out of the bushes [or] crawling in the window at night,” Donegan said. “Those are a small percentage of our cases.”

Garrett said one of the biggest reasons she felt police took her case more seriously was because her attacker was a stranger. She said if it had been someone she knew, she’s not sure if she would have been believed or if she would have spoken out.

Donegan said victims are more likely to report their rapes if they were committed by strangers, and those cases tend to be prioritized. This means many police officers are less equipped to handle the complexities of a nonstranger case.

Officers still rely too heavily on DNA analysis when investigating these cases, for example, but forensic evidence is usually needed only to prove the identity of a suspect or if sexual contact occurred.

More often than not, especially in acquaintance rapes, the focus of an investigation is overcoming the nearly invincible defense that the sex was consensual. To make an arrest, police need to , which often puts the burden of proof on the victim.

“Unfortunately, in many instances, victims are the ones that are on trial,” Donegan said. “From the moment they choose to tell someone, their credibility and believability is challenged. We need to shift that paradigm, we need to shift the understanding, about what real sexual assault is and what that looks like."

Even if Austin police believe there is enough evidence to overcome the consent defense, it’s up to the Travis County District Attorney’s Office to ultimately decide whether to prosecute. Donegan said she believes APD would have more arrests if more prosecutors were willing to take the nonstranger cases forward. From her perspective, bringing more of these cases “will help educate the public” that these types of sexual assaults make up the majority of cases.

The Austin Police Department has two Travis County prosecutors it uses to staff cases. When it comes down to whether a DA thinks a case is prosecutable, Austin Assistant Police Chief Joseph Chacon says, "their opinion weighs heavily on us."

_________________

The Provability Gap episodes:

If you or anyone you know needs help following a sexual assault, call the 24-hour SAFEline in Austin at 512-267-SAFE (7233) or the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE (4673).

Copyright 2020 KUT 90.5. To see more, visit . 9(MDAxODQzOTgwMDEyMTcyNjI4MTAxYWQyMw004))