Willis Chun was barely a toddler when his father, Wah Chun, the owner of Chan’s Chinese Cottage, would dress him up in a suit and bowtie to bring him to the restaurant to greet customers.

The air smelled of egg rolls fresh out of the fryer and was filled with the sound of Chinese and English being bounced back and forth from the waitstaff to the chefs in the kitchen. Amid the hustle and bustle, Willis would sneak off into the back and treat himself to a few crispy noodles — luckily, his father never found out.

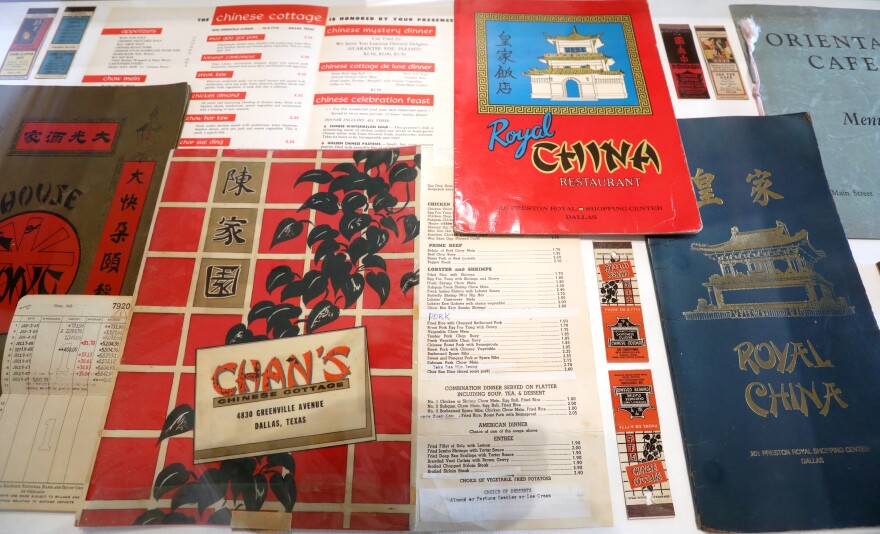

A menu from Chun’s family restaurant is featured in The Dallas Asian American Historical Society’s first exhibition: “Leftover: The Enduring Legacy of Chinese Cuisine in Dallas.” The exhibition seeks to preserve the history of Chinese American restaurants and the stories of the people who built them.

“This was sitting in my photo album in my closet,” Willis Chun says, pointing to the menu book, which is now in a display case at the exhibit. “There are people in my own family who don’t know about this stuff.”

The Chinese Cottage first opened in 1942 on Haskell Avenue, and in 1952 moved to a location on Greenville Avenue. In addition to the chow mein and moo goo gai pan, his father’s restaurant featured an item called “Chinese mystery dinner.”

It wasn’t some secret recipe from the Toisan region of China, where Chun’s ancestors are from. The menu item was made for regular patrons looking for a new twist on previous dishes. It was more than a marketing gimmick. Chun says it’s proof of the relationship his father built with his customers, many of whom had little exposure to Chinese cuisine.

Chun knows some people today might roll their eyes at some of the Chinese cuisine his father’s restaurant served, written off as “Americanized” or stripped of authenticity; it’s a theme he’s had to grapple with his own Asian American identity.

“But who gets to say what’s authentic?” he asks.

A quick Google search of dishes commonly served at Chinese American restaurants like chop suey and General Tso’s chicken reveals a mix of origin stories, some of which are more culinary myth than historical fact.

Although it’s true that Chinese chefs adjusted their recipes to cater to American palates, Stephanie Drenka, co-founder of the Dallas Asian American Historical Society, says she wants the exhibition to shine a different light on the restaurants that, in many ways, paved the way for other Asian cuisines styles.

“We wanted to challenge people’s notions of who or what gets to be considered Asian enough or American enough,” she says.

The exhibition shows how Chinese American history is inseparable from Dallas history.

On one of the walls of the exhibition hangs a tapestry showing, in part, the history of Chinese Americans in Texas. History that dates back to the 1870s, when the first people of Chinese descent came to the state as railroad workers.

A different part of the exhibition features a photo album with residents who were integral to the city's Chinese American restaurant scene, like Buck Jung, who started a company in 1952 that supplied egg roll wrappers, noodles and other ingredients used at Chinese American restaurants.

Michael Yee, who attended a private opening of the exhibition along with Jung and other families whose histories were featured, says he has a new appreciation for how people like his grandfather, who owned and operated the Lim Yee Cafe in Old East Dallas, created a community in North Texas.

“They did what they had to do to survive in their new home country,” Yee says.

That community is at the heart of the exhibition, Drenka says. It’s not just an exhibition about Chinese food, it’s about the people and the identities connected to it.

“We’ve been so deprived of histories and stories that speak to things like that,” Drenka says. “For the families and people who are featured in the exhibit, I hope it really solidifies and affirms their family pride."

Details: “Leftover: The Enduring Legacy of Chinese Cuisine in Dallas” continues through September 22 at Preservation Dallas’ Wilson House.

Arts Access is an arts journalism collaboration powered by The Dallas Morning News and �Ļ�ӰԺ.

This community-funded journalism initiative is funded by the Better Together Fund, Carol & Don Glendenning, City of Dallas OAC, Communities Foundation of Texas, The Dallas Foundation, Eugene McDermott Foundation, James & Gayle Halperin Foundation, Jennifer & Peter Altabef and The Meadows Foundation. The News and �Ļ�ӰԺ retain full editorial control of Arts Access’ journalism.